The Pyramid and Coffin Texts comprise a collection of sacred writings from ancient Egypt, believed to be crucial for guiding the dead on their journey to the afterlife. These texts, discovered on tomb walls and within coffins, offer insights into ancient Egyptian religion, mythology, and cosmology.

Writing stands out as a prominent feature of ancient Egyptian culture, evident in nearly every artifact crafted by the ancient Egyptians. Serving as a symbol of authority, writing was closely associated with royal power. Therefore, it’s remarkable that, despite its mortuary function, writing appears later in the tombs of kings compared to those of other members of Egyptian high society.

During the IV dynasty, mastabas (private tombs) already bore inscriptions dedicated to the mortuary offerings of the deceased, while the royal tombs of that era, notably the famed pyramids of Giza, lacked any written inscriptions for such purposes. This remains a puzzling aspect of ancient Egyptian archaeology.

However, in a curious turn of events, toward the end of the subsequent dynasty (the V), a king ordered the interior of his tomb to be inscribed with a complex set of texts.

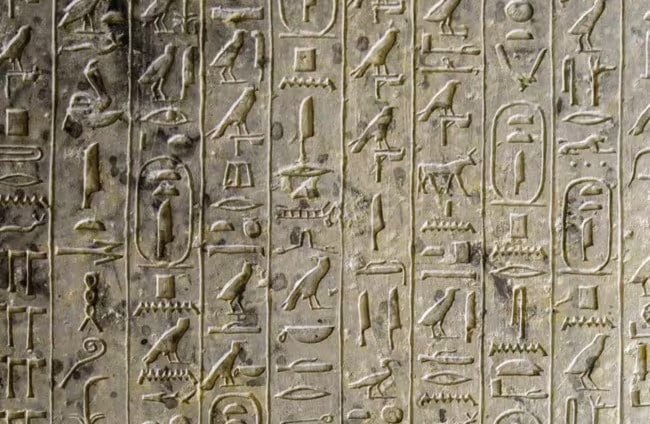

These texts commence just at the end of the descending corridor, which grants access to the antechamber, and they continue uninterrupted on both sides of the tomb’s interior, covering the first two-thirds of the side walls of the sepulchral chamber.

While the back wall of the sepulchral chamber (excluding its upper part) and the last third of its side walls lack texts, they instead feature a decorative motif resembling a palace façade, much like the sarcophagus, which remains in its original placement.

These texts, carved into the limestone walls and painted in a greenish-blue hue that the Egyptians associated with the afterlife, are known in Egyptology as the Pyramid Texts, comprising 922 “formulas” or chapters.

The king associated with these texts is Unas, and his tomb—a pyramid—can be visited in the necropolis of Saqqara, one of the principal burial grounds of Memphis, the great Egyptian capital during the Old Kingdom, situated in the Nile Valley near the southern apex of the delta, connecting Upper Egypt (the valley) and Lower Egypt (the delta).

Around the same time (early 6th dynasty), approximately six hundred kilometers southwest, deep within the Sahara Desert, in the Dakhla Oasis, similar texts are found in the tomb of a priest named Medunefer, located in a settlement known today as Balat.

These texts, also funerary in nature, belong not to a king but are written in ink on stucco (rather than engraved in stone) and likely formed part of the wooden coffin of the deceased.

Such texts are prevalent on the wooden coffins of dignitaries from the Middle Kingdom (11th and 12th dynasties), five hundred years later.

Hence, the term Coffin Texts was coined for them (with 1185 known formulas to date). Somewhat inaccurately, they are also referred to as the Sarcophagus Texts.

While both groups of texts seemingly emerge around the same period based on archaeological findings, it is widely accepted in Egyptology that the Pyramid Texts precede the Coffin Texts, indicating two distinct textual groups.

This understanding is supported by the appearance of a third group of texts known as the Book of the Dead (or Book of Coming to Day, as it appears the ancient Egyptians knew it), which emerges after the Middle Kingdom during the Second Intermediate Period, typically inscribed in ink on papyrus scrolls.

The concept of the three groups of texts is rooted in the archaeological and chronological variances we’ve outlined, yet the content and purpose of the texts allow them to be viewed as a unified whole.

This textual tradition emerges as early as the V dynasty and persists throughout ancient Egyptian history with the aim of safeguarding and benefiting the deceased.

With few exceptions, these texts were inscribed in the private areas of the tomb, where the deceased lay alone. They were never intended for reading, although some may have been recited in connection with the death and funeral rites of the deceased, always appearing in close proximity to the embalmed corpse.

Indeed, they became increasingly intimate: initially found on the walls of the sepulchral chamber, then on the inner surfaces of the coffins (sometimes the deceased would have multiple coffins nested within each other), and finally on a papyrus scroll placed inside the coffin, in direct contact with the mummy.

The Name of the Deceased

The texts exhibit a wide range of content and are often intricate, making them challenging to decipher, yet they share several commonalities. Their exclusive, direct, or quasi-direct association with the deceased suggests that the texts pertain to the individual interred. This inference is reinforced by the presence of the deceased’s name within the texts.

Frequently, errors in the texts indicate that many were originally penned in the first person, as if the deceased were addressing a divine entity, only to later be altered to the third person. This editorial modification is perplexing, but likely serves two purposes: personalizing the text and acknowledging the presence of the name within the tomb.

Personalization is crucial for identifying the deceased both in the afterlife and within the necropolis. The ba, a component of the deceased believed to transcend biological death, serves as the link between the deceased and the living world, departing the tomb each day to reunite with the mummy at night. Hence, reference to the name is imperative.

Regarding the presence of the name within the tomb, it holds inherent significance because the name (ren) is among the elements separated from the deceased upon biological death (considered the first death from the Egyptian perspective), alongside the ba, shadow (shut), ka, and mummy (sah). According to ancient Egyptian beliefs, death constitutes a disruption of life rather than its termination, resulting in the disconnection of these vital elements. Each plays a distinct role in maintaining the deceased’s connection with the living.

While the ba sustains contact with the living, the ka receives offerings, and the mummy ensures the physical presence of the deceased within the tomb, the name persists within the texts, both in the public and private areas of the tomb. These texts, bearing the name of the deceased, not only serve to identify them but also provide protection in the grave and likely extend into the afterlife.

Because the deceased does not remain in the grave; they proceed westward, sinking into the earth, to undergo a trial before Osiris, the god of death and resurrection.

In Egyptian mythology, the weighing of the heart on a scale introduces the possibility of a second death, which the deceased must overcome with the aid of specific texts known as “formulas of transfiguration.” These formulas, recited by a specialized priest (the reader priest), aim to transform the deceased into an akh: a radiant entity (as implied by the term akh) that ascends to the realm of the gods, residing in the Field of Reeds. This realm bears a striking resemblance to earthly Egypt, facilitating contact with the divine beings. As an akh, the deceased becomes beneficial (another connotation of akh) to their living relatives.

Another crucial set of texts for the deceased in the afterlife is the “transformations.” These formulas, found in the Coffin Texts and continuing into the Book of the Dead, are seemingly devoted to ensuring that the deceased surmounts obstacles and outwits adversaries in the postmortem realm by assuming various forms, ranging from gods to animals, plants, and even natural elements like fire. In this realm where the deceased confronts death repeatedly, the texts discussed here serve as potent tools, akin to the tomb itself, the embalming process, or the offerings brought by the living.

A common aspect of all these texts is their apparent reuse. Not only those recited during funerary or mortuary rituals but all of them. The magical texts designed to ward off snake attacks or hymns to divinities—what purpose do they serve for the deceased?

Judging by their content, seemingly none. It is likely their mere presence that holds significance and utility. This intricate process of transforming and adapting these oral or written statements—whether mortuary or not—onto tomb walls, coffins, and sarcophagi is referred to as “entextualization.”

The Genesis of a Lengthy Textual Tradition

Another notable common element is the dialogue prevalent throughout the majority of these texts, established between the deceased or their representative (often an officiant, typically the deceased’s son) and divine or semi-divine entities, or between the officiant and the deceased. Many of these dialogues reflect a well-known situation of exchange or negotiation, succinctly summarized in the Latin adage “Do ut des” (“I give so that you give”).

On one hand, the akh enters a realm—the divine domain—that is inherently hostile, requiring negotiation for its right to entry. It must legitimize itself before divine entities who may not readily accept it and with whom it may even need to compete. On the other hand, the officiant provides offerings to appease the deceased. Notably, the Egyptian term hetep conveys both “offering” and “satisfaction” or “appeasement.”

Lastly, the Pyramid Texts and the Coffin Texts mark the initial emergence of repositories of sacred texts designed to safeguard and benefit the deceased, both within the necropolis and on their journey beyond death. This marks the inception of an extensive textual tradition that persisted throughout Egyptian history, notably with the Book of the Dead, along with other specialized “books” with more limited usage (such as the Amduat, Gates, and Caverns).

These texts existed alongside one another, with the oldest texts alongside more recent ones, systematically intermixed, copied, and reused. There was never a strict canon; these were not truly books, despite our terminology, but rather collections of texts.

In essence, they form an exceptional corpus that prompts reflection on our notions of what constitutes a text or a book, a document or a monument. It underscores the necessity for extreme caution when applying such distinctions (and others) to cultures vastly distant from us in time, space, and mentality.

Source: Carlos Gracia, Egyptologist (muy interesante)

#Key #Understanding #Ancient #Egyptian #Religion