How the Nation’s First ‘Madam Secretary’ Fought to Save Jewish Refugees Fleeing From Nazi Germany

:focal(1350x1080:1351x1081)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/75/90/7590f6ee-d27b-4ca0-804c-498728f55919/2700px-thumbnail.jpg)

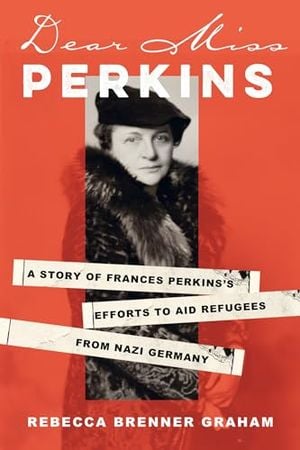

A 1937 photograph of Frances Perkins, the first female cabinet secretary in American history

Public domain via Wikimedia Commons

She nearly missed the president’s inauguration, but when she got there, she stole the spotlight.

On a mud-swept afternoon in March 1933, Washington, D.C. reporters thronged around Frances Perkins, the newly appointed secretary of labor under President Franklin D. Roosevelt. It had been a hard first day, full of taxi delays and a rushed first meeting with her fellow cabinet secretaries, all men. The press badgered her with questions, like “What do we call you?” They wondered how the first-ever “Madam Secretary” might guide a nation fighting its way out of a bitter economic crisis.

“Perkins was no Washingtonian,” writes historian Rebecca Brenner Graham in her new book, Dear Miss Perkins: A Story of Frances Perkins’ Efforts to Aid Refugees From Nazi Germany. The labor secretary’s outsider status paid off. A social worker turned cabinet star, Perkins is often credited as the “woman behind the New Deal.” She designed many policies that Roosevelt chalked up as big wins, weathering his entire administration in her trademark tricorne hat and pearls. She helped to push landmark laws through Congress, including the Social Security Act of 1935, the National Labor Relations Act of 1935 and the Fair Labor Standards Act of 1938.

But as Nazi Germany relentlessly persecuted Europe’s Jews, leading refugees to seek haven in America, Perkins’ job—which found her overseeing the Immigration and Naturalization Service—changed overnight. Thousands of letters pleading for aid flooded her desk. Patiently, she thought through each one.

Faced with racist quotas and restrictive laws, Perkins dared public condemnation—even enduring a congressional crusade for her impeachment—in a desperate effort to save refugees and relocate them to the United States. “Could the U.S. be a refuge to oppressed people? Did it want to be?” Graham writes of Perkins’ immense challenge. “Could it overcome its own prejudices to be ‘the golden door’”?

To mark Dear Miss Perkins’ release on January 21, Smithsonian chatted with Graham to learn how Perkins readied New Deal America to welcome refugees. Read on for a condensed and edited version of the conversation.

Perkins, circa 1915 to 1920/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/a8/bc/a8bc278d-a490-46f9-b6d1-fa755361a587/1599px-frances_perkins_lccn2014708218.jpg)

How did you first learn about Frances Perkins? How did her social work experience prepare her for the president’s cabinet?

Many people may not have heard of the first woman cabinet secretary in U.S. history. I first heard of Perkins because she was Mount Holyoke College class of 1902, and I was the class of 2015. Sponsored by the Frances Perkins Center, as a rising senior I organized journalist and biographer Kirstin Downey’s huge collection of photocopied research for donation to the archives. Sorting through Kirstin’s papers and reading her book The Woman Behind the New Deal, I “met” Perkins.

Perkins was born in Boston, raised in Worcester and educated at Mount Holyoke. She came of age through work in settlement houses and graduate work in economics and sociology in Chicago, Philadelphia and New York. Roosevelt nominated Perkins as secretary of labor in part because she’d most recently served as industrial commissioner for New York State during his gubernatorial administration. A culmination of her experiences in women-centered labor movements and social activism prepared Perkins for service at state and national levels.

Which mentors and allies were key to Perkins’ success?

Perkins built strong relationships with other people, especially women. A few stand out. Her Mount Holyoke history professor Annah May Soule took students to local mills to expose upper-middle-class students like Perkins to the difficult working conditions, demonstrating that poverty was not poor people’s fault. Soule was an innovative teacher and a well-connected member of early 20th-century activism movements. Florence Kelley was a social reformer who campaigned against child labor and for a minimum wage. She mentored Perkins, who shaped the New Deal legislation enacting those measures.

Social reformer Florence Kelley appears third from left in this 1914 photo of female factory inspectors./https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/bc/c4/bcc455a8-99c3-44ac-9b36-84a508c0c7c2/1514px-thumbnail.jpg)

When Cecilia Razovsky heard about Perkins’ interest in the German Jewish refugee crisis in 1933, Razovsky mobilized Jewish activist networks to create the German Jewish Children’s Aid. Razovsky’s organization collaborated with the Children’s Bureau in Perkins’ Department of Labor on a robust child refugee program. Razovsky and her team canvassed Jewish communities for fundraising and lodging for the children. Perkins provided a government structure to back them.

What do we know about Perkins’ politics? And what was her relationship with Roosevelt like?

Perkins and Roosevelt shared both an Episcopalian faith and a Democratic belief in the role of government to help people in need. “I have done what I could in time to make this great country of ours a little nearer our conception of the City of God,” she told Congress in 1939, when members attempted to impeach her for not deporting someone they didn’t like. These shared political and religious values drove their work, even when Roosevelt could not or would not protect Perkins’ initiatives. Perkins did not keep a diary. However, she occasionally left an illegible “note to self” in her papers. For example, after sitting through hearings on a resolution to impeach her in 1939, Perkins scribbled a disconnected set of words: “Integrity.” “Democracy.” “Fair treatment.” “Without oppression.” “Men of conscience.” Those were some of her values.

Dear Miss Perkins traces how immigration law intersected with refugee policy. How did Perkins effect change?

United States law did not define “refugee” until 1980. And existing U.S. immigration law during this period focused on restricting immigration. One of Perkins’ first tasks as labor secretary was to reform immigration practices within her department. She asked Roosevelt for an executive order combining the Immigration Bureau with the Naturalization Bureau to create the Immigration and Naturalization Service in 1933, and he obliged. Then, she worked with the commissioner of immigration and an Ellis Island Committee to humanize the experience of entering the country. Reorganizing the bureaucracy and creating new norms enabled Perkins’ subsequent efforts on behalf of refugees through corporate affidavits, visa extensions and more. In turn, Perkins’ actions helped to secure refuge for tens of thousands of people under restrictive laws.

Jewish refugees aboard the M.S. St. Louis, a ship that sought safety in both the U.S. and Canada in 1939, only to be denied/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/8a/bf/8abff49a-b801-4582-9cb4-a2a1435e5317/11291-s.jpg)

Tell us about reading the thousands of letters that Jewish refugees sent, seeking federal aid.

Perkins received letters on behalf of refugees from mutual acquaintances she met throughout all stages of her life and career. For example, the journalist Dorothy Thompson wrote to her on behalf of a refugee she knew in Los Angeles. A philanthropist at Hull House, where Perkins had volunteered as a young adult, wrote for help navigating the system to sponsor the immigration of a refugee.

Perkins’ dentist, Eugene Weissmann, wrote her to help his cousin, Endre Varady, who was trapped in Nazi territory with his Jewish family. In Varady’s case, Perkins was unable to intervene because Varady was born in Hungary, and the immigration of his family depended on where he was born according to the National Origins Act of 1924. There was a decade-long waitlist for Hungarian immigrants that only Congress could alter. As a regular businessman, too, Varady did not qualify for a non-quota visa. A reference librarian at the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum used databases to tell me that Varady and his family survived by immigrating to New Zealand.

The “Dear Miss Perkins” letters in the Labor Department records at the National Archives at College Park, from which I gleaned individual refugee stories, collectively demonstrate a piecemeal system reliant on the humanity and compassion of the person in charge.

What was the Alaska plan, and how did it change government thinking on refugee policy?

In 1940, lawmakers in Congress and in the Interior Department considered opening a separate quota for immigration to Alaska. The idea was for Jewish refugees from Europe to settle and economically develop the sparsely populated, colonized territory. Perkins’ role in the plan was that she corresponded with individuals on the ground in Alaska on this topic as early as 1935, and she was at least one of the people who suggested the idea to Secretary of the Interior Harold Ickes. The Alaska story represents Perkins’ tireless brainstorming of ways to help and also, perhaps, her blind spot to a more sinister history of American settler colonialism. Neither Indigenous Alaskans nor the Jewish refugees had a real say in the discussions.

Perkins and President Franklin D. Roosevelt in 1943 FDR Presidential Library and Museum via Wikimedia Commons under CC BY 2.0/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/80/08/8008bed0-8984-4ca6-91ba-d6a50c7d7a42/1746px-president_roosevelt_welcomed_home_from_the_teheran_conference_61-701.jpg)

Perkins was also a biographer—of her boss, the 32nd president. How did she handle the task?

Perkins did not seek out the opportunity to publish a biography of Roosevelt. A literary agent, who chased her down on a trip to London, pitched the idea. “Don’t be so stupid,” Perkins’ daughter, Susanna, admonished her. The advance from Viking was more than Perkins’ government salary, and she needed the money to support her family. In The Roosevelt I Knew, Perkins often edits herself out, repeatedly crediting to the president whatever she advised him to do. Published in 1946, The Roosevelt I Knew is emblematic of Perkins’ strong opinions on what to do, without soliciting public credit.

Is there anything else that you’d like Dear Miss Perkins readers to know and think about more?

This is a story of collective and individual action. Individually, Perkins tried to do as much as possible to help refugees. Collectively, American institutions and the public comprised the odds stacked against her. Perkins believed in creating collective structures and institutions to help people in need, through the New Deal, and again through her efforts to aid refugees from the immeasurable and unfathomable tragedy of Nazi Germany.

A Note to our Readers

Smithsonian magazine participates in affiliate link advertising programs. If you purchase an item through these links, we receive a commission.

#Nations #Madam #Secretary #Fought #Save #Jewish #Refugees #Fleeing #Nazi #Germany