Barbary Corsairs, the Infamous Seaborne Plunderers

In ancient times, life on the open seas and the coasts was far from peaceful as it is today. For all the open waters were ripe for plunder – by pirates thirsty for loot. One of these pirate groups of ancient times were the Barbary Corsairs, also known as Barbary pirates or Ottoman corsairs. They were infamous privateers and plunderers who operated from the North African coast, particularly from the ports of Algiers, Tunis, Tripoli, and Salé.

These pirates were active from the late 15th century AD until the 19th century, terrorizing the Mediterranean Sea and even reaching the Atlantic Ocean. Their activities had significant impacts on the European powers and their colonies, shaping maritime law and international relations alike. These corsairs were predominantly Muslim and worked under the auspices of the Ottoman Empire, though they often acted with considerable independence. Eventually their infamous activities were curtailed.

Barbary Corsairs, the Menace of the Mediterranean

The rise of the Barbary Corsairs is rooted in the complex political and religious landscape of the Mediterranean following the Reconquista, the period in which the Christian kingdoms of the Iberian Peninsula reconquered territory from the Muslims.

With the fall of Granada in 1492 AD, many Muslims and Jews fled to North Africa, contributing to the growth of piracy. The weakening of centralized Muslim rule in North Africa created an environment where piracy could thrive. As Spain and Portugal began to expand their influence into the Maghreb, local rulers saw the corsairs as a means to counterbalance Christian power and maintain regional autonomy.

During this time, the Ottoman Empire was expanding its reach into North Africa. The Ottomans provided the corsairs with protection and resources in exchange for allegiance and tribute, viewing the corsairs as a strategic tool to project power in the Mediterranean. The most famous of these alliances was with the brothers Aruj and Hayreddin Barbarossa, who became legendary figures in the history of the corsairs.

The Barbarossa brothers captured Algiers in 1516, establishing it as a major corsair base under Ottoman protection.

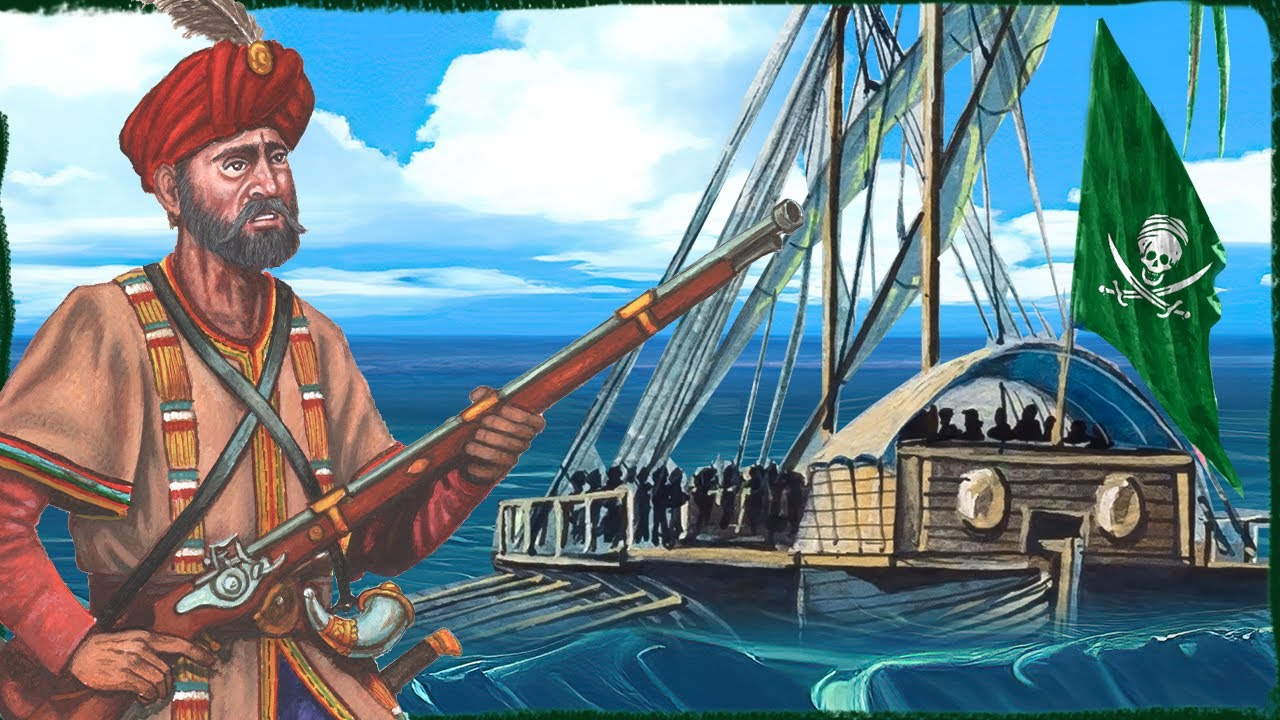

An Algerine pirate ship (Public Domain)

The Barbary Corsairs operated primarily as privateers, sanctioned by their home governments to attack foreign ships and coastal towns. This legal status distinguished them from pirates, who were considered outlaws. The corsairs were skilled sailors and navigators, often using small, fast vessels like galleys and xebecs, which allowed them to outmaneuver larger ships. Their ships were equipped with oars and sails, enabling them to pursue or escape under various wind conditions.

Aruj, or Oruç, Reis was a Turkish privateer and later Admiral in Ottoman service who became known as Barbarossa – or Redbeard – amongst Christians. (Public Domain)

Wolves on the Waves

A typical corsair attack involved surprise and speed. They targeted merchant ships carrying valuable cargo, often preferring to capture rather than sink them. This approach allowed the corsairs to ransom captured crews and passengers back to their home countries. Many European powers, recognizing the threat, began paying tribute to the Barbary states to ensure safe passage for their ships. These payments became a significant source of income for the corsairs and their sponsors.

In addition to maritime raids, the Barbary Corsairs also launched attacks on coastal towns across Europe, from Italy and Spain to as far north as Iceland. These raids were aimed at capturing slaves and plundering wealth. The corsairs took thousands of captives over the centuries, selling them in the thriving slave markets of North Africa. This practice contributed to a complex economy centered around human trafficking, and the ransoming of captives became a diplomatic issue between European powers and the Barbary states.

The activities of the Barbary Corsairs had profound political and economic impacts on both Europe and North Africa. For the Barbary states, the corsairs provided a crucial source of income and military power. The wealth acquired through piracy helped to sustain the local economies, fund public works, and pay for military defenses. The corsairs also played a role in the internal politics of the Barbary states, often holding considerable influence over local rulers and sometimes even acting as de facto leaders themselves.

For European powers, the threat posed by the corsairs forced significant changes in naval strategy and foreign policy. The need to protect merchant shipping led to the development of more sophisticated naval technologies and tactics. Many European states, unable to suppress the corsairs through military means alone, resorted to diplomacy and tribute payments. These payments, while burdensome, were often seen as a necessary cost of doing business in the Mediterranean.

Bombardment of Algiers by Lord Exmouth in August 1816, Thomas Luny (Public Domain)

To Live by the Sword

The corsairs’ activities also spurred European powers to form alliances and coalitions to combat the threat. The Holy League, a coalition of Catholic maritime states, was formed in the late 16th century to confront Ottoman naval power and its corsair allies. The league’s victory at the Battle of Lepanto in 1571 marked a significant turning point, curbing Ottoman expansion in the Mediterranean but doing little to eliminate the corsair threat.

Religion played a significant role in the activities of the Barbary Corsairs. The conflict between Christian Europe and the Muslim world of North Africa and the Ottoman Empire was framed in religious terms, with the corsairs often seen as holy warriors or ghazis fighting against infidels. This religious dimension was used to justify the corsairs’ attacks on Christian ships and settlements, and it attracted many Muslims to their cause, including converts and renegades from Europe.

Conversely, the religious conflict also fueled European animosity towards the corsairs, casting them as pirates and barbarians. This perception was reinforced by the corsairs’ practice of slavery, which often involved the capture and sale of Christians. Religious orders such as the Trinitarians and the Mercedarians were established in Europe to raise funds for the ransom of Christian captives, highlighting the religious and humanitarian dimensions of the conflict.

British captain witnessing the miseries of Christian slaves in Algiers, 1815 (Public Domain)

The decline of the Barbary Corsairs began in the late 18th century, as European powers increased their naval capabilities and sought to assert control over the Mediterranean. The Napoleonic Wars disrupted the balance of power, leading to a series of conflicts between the Barbary states and European countries. The United States, too, became involved, fighting the First and Second Barbary Wars in the early 19th century to stop the corsair attacks on American shipping.

The decline of the Ottoman Empire also contributed to the corsairs’ waning influence. As Ottoman control over North Africa weakened, the corsair bases lost their primary source of support and legitimacy. European colonial expansion into North Africa in the 19th century marked the end of the Barbary Corsairs as a significant force. The French conquest of Algiers in 1830 was a decisive blow, effectively ending piracy in the region.

Legendary Sea Raiders

Despite their decline, the legacy of the Barbary Corsairs remains significant. Their activities influenced the development of international maritime law, contributing to the eventual abolition of piracy as a legitimate form of warfare. The corsairs also left a lasting cultural impact, inspiring works of literature and art, and shaping the popular image of pirates as exotic and fearsome figures. The Barbary Corsairs have left an irreplaceable mark on cultural history, with their exploits immortalized in literature, art, and folklore. The corsairs were often depicted as romanticized figures in European literature, embodying both the allure and danger of the exotic East. Works such as “The Corsair” by Lord Byron captured the imagination of readers, drawing on the mystique of the pirates to explore themes of heroism, rebellion, and adventure.

A Barbary pirate, Pier Francesco Mola, 1650 (Public Domain)

In North Africa, the legacy of the corsairs is intertwined with national and regional identity. They are often remembered as defenders of Muslim lands against European aggression, and their stories are part of the cultural heritage of countries like Algeria, Tunisia, and Libya. The corsairs’ influence is also evident in the architecture and urban landscapes of former corsair bases, where forts, kasbahs, and harbor defenses testify to their historical presence.

The Barbary Corsairs’ effectiveness was partly due to their innovative use of technology and naval tactics. Their ships, often smaller and more maneuverable than those of their adversaries, were equipped with both sails and oars, allowing them to operate independently of the wind. This flexibility made them formidable opponents, capable of executing swift attacks and rapid retreats.

The corsairs were also skilled in the use of artillery, employing cannons on their ships to outgun their prey. The development of ship-mounted cannons in the late 16th century gave the corsairs a significant advantage over merchant vessels, which were often lightly armed or unarmed. This technological edge, combined with their knowledge of Mediterranean currents and weather patterns, allowed the corsairs to dominate the seas for much of their history.

A Tricky Seaborne Enemy

European responses to the corsair threat included advancements in naval design and armament. The development of larger, more heavily armed warships was a direct response to the need for better protection against pirate attacks. These innovations contributed to the rise of powerful navies in countries like Spain, France, and Britain, which would eventually challenge and suppress the corsairs’ activities.

One of the most tragic aspects of the Barbary Corsairs’ activities was the human cost, particularly the widespread practice of slavery. The corsairs captured thousands of people from European ships and coastal towns, selling them in slave markets across North Africa. Captives included men, women, and children, who faced brutal conditions and uncertain futures. The slave trade was a significant source of income for the corsairs and their patrons. Wealthy individuals and governments paid large ransoms to secure the release of captives, while those unable to pay were often forced into labor or sold as slaves in other regions. The demand for slaves fueled the corsairs’ raids, creating a cycle of violence and suffering that lasted for centuries.

The Slave Market. (Public Domain)

The impact of slavery extended beyond the immediate victims, affecting families and communities across Europe. The fear of corsair attacks and the threat of enslavement loomed large in the minds of coastal populations, influencing local economies and ways of life. The memory of these raids remains part of the historical consciousness in many parts of Europe, shaping perceptions of the Mediterranean and its complex history of conflict and exchange.

Pirates of the Mediterranean

The story of the Barbary Corsairs is no doubt a tale of adventure, conflict, and cultural exchange. Operating at the crossroads of Europe, Africa, and the Ottoman Empire, the corsairs played a significant role in the history of the Mediterranean, shaping the course of maritime trade and international relations for centuries. Their activities had profound impacts on the political and economic landscapes of the time, influencing the development of naval power, international law, and diplomatic relations.

And though often portrayed as ruthless pirates, the Barbary Corsairs were also products of their environment, navigating the complex interplay of religion, politics, and commerce in a tumultuous era. Their legacy is a testament to the enduring power of the sea to connect and divide human societies, and a reminder of the intricate histories that have shaped the world we live in today.

Top image: A sea fight with the Barbary corsairs. Source: Public Domain, Public Domain

By Aleksa Vučković

References

Earle, P. 2003. The Pirate Wars. Thomas Dunne.

Forester, C. S. 1953. The Barbary Pirates. Random House.

Heers, J. 2003. The Barbary Corsairs: Warfare in the Mediterranean, 1480–1580. Greenhill Books.

#Barbary #Corsairs #Infamous #Seaborne #Plunderers