Nvidia’s RTX 50-series drivers feel half-baked, focus too much on MFG

Releasing a new GPU architecture is a complex affair. Nvidia should know this as well as any company, considering it’s been making graphics cards for 27 years now, every one of which needed drivers. But the Nvidia Blackwell RTX 50-series GPUs haven’t had the smoothest of launches. The RTX 5090 at least offers new levels of performance, while the RTX 5080 delivers only slightly better performance than the prior generation RTX 4080 Super. But both GPUs seem to be suffering from a case of early drivers and the need for additional tuning.

It’s not just about drivers, though — or perhaps it is, but for Blackwell, Nvidia recommends new benchmarking methodologies. It presented a case at its Editors’ Day earlier this month for focusing more on image quality and analysis, which is always a time-consuming effort. But it also recommended switching from PresentMon’s MsBetweenPresents to a new metric: MsBetweenDisplayChange (which I’ll abbreviate to MSBP and MSBDC, respectively).

The idea is that MSBDC comes at the end of the rendering pipeline, right as the new frame actually gets sent to the display, rather than when the frame finishes rendering and is merely ready to be sent to the display. It’s a bit nuanced, and in theory, you wouldn’t expect there to be too much of a difference between MSBDC and MSBP. Intel has also stated that MSBDC is the better metric and recommended using it for the Arc B580 and Arc B570 launches.

Part of the issue with MSBP is that it doesn’t necessarily capture information correctly when looking at frame generation technologies. And, in fact, if you try to use MSBP with Nvidia’s new MFG (Multi Frame Generation), you get garbage results. This wasn’t the case with DLSS 3 framegen, but MFG reports data in a different manner:

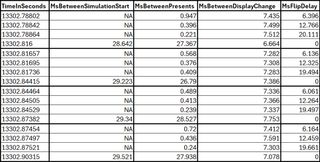

All of the fields shown are useful data, but with MFG 4X the values in the MSBP column now function differently. You can view it as the total time required for the GPU to render the frame in the traditional manner, so in this case, it’s about 27.66 ms per frame, followed by nearly instant “rendering” times for the three generated frames. The new flip metering hardware in Blackwell GPUs then attempts to evenly pace the actual display of the generated frames on your monitor.

Looking at the MSBDC column, we find a far more consistent sequence of frametimes, as expected. Instead of the “fast-fast-fast-slow” frametimes in the MSBP column, we get relatively similar frametimes of around 7.35 ms per frame. The MsBetweenSimulationStart column ends up giving the timing of user input sampling. So, in this case, the user input sampling happens every 29.18 ms, or at 34.3 FPS, while the generated rate of unique frames sent to the monitor runs at 136.1 FPS — basically four times the input sampling rate, as expected.

The above results, incidentally, are taken from Cyberpunk 2077 benchmarks running at 4K with the RT-Overdrive preset (aka path tracing or full RT), DLSS Quality Transformers upscaling, and MFG4X frame generation. As I noted in the 5080 review, the smoothness of the framerate as seen on the monitor does make the game feel better than if it were running at 34 FPS, but it also doesn’t feel like it’s running at 136 FPS because input sampling is happening at the base framerate of 34.

But back to the discussion of MSBP and MSBDC, it’s a relatively easy “fix” to switch between the two metrics. Also, without using framegen of any form, we’d expect the resulting performance metrics to look pretty similar. But “similar” isn’t the same as “identical,” and since I already had all of this data, I decided to take a closer look at what’s going on and how the new metric affected my benchmark results. It’s probably not going to be what you’d expect…

The above gallery shows the 14 graphics cards I’ve tested (so far…) using our new test suite and PC. There are 22 games, six of which have ray tracing enabled and 16 that are running in pure rasterization mode. Each image shows the same GPU, using the MSBDC metric compared to MSBP, and the third column is the import one as it shows the percentage change — how much better or worse MSBDC is compared to MSBP.

The average framerates are as expected. Whether you measure at the start or end of the rendering process, overall the total time averages out to the same value. There are differences, however, as the data in MSBDC sometimes doesn’t appear useful. There are MSBDC values of 0.000 ms at times, and this throws off my formulas, so I just tossed those values.

“Instant” frametimes would pull the average FPS up if included, but I’m not sure what they’re supposed to represent, as obviously it should take some amount of time to render and display the next frame. Are they dropped frames or something else? It’s not clear, so I asked Nvidia for feedback, as I’m using its FrameView utility to capture these benchmarks. Note also that the lower spec cards (RTX 4060/3060, the Arc cards, and AMD’s 7600/XT/6600) were all tested last month using an older version of FrameView that appears to have been more prone to have 0.000 results for MSBDC.

But really, the changes in the 1% lows are interesting to look at. All of the Intel Arc GPUs show improved 1% lows, increasing by up to 8.3% on average. That’s a pretty decent improvement for what would otherwise seem to be a relatively minor change in how performance gets measured. The RTX 3060 and 4060 also show modest improvements, and these were tested with older 566.36 drivers. AMD’s GPUs also show modest improvements in minimum FPS.

And then we get to the newer Nvidia cards, which were tested with preview 571.86 — and 572.02 drivers on the 5080. The 4080 Super, 4090, and 5090 all show worse 1% lows at 1080p medium/ultra, and equal or slightly better minimums at 1440p and 4K. The 5090, on the other hand, sees worse typical 1% lows at 1080p and 1440p, and basically equal minimums at 4K. There are plenty of games that show a marked drop in 1% lows as well, while a few see a modest increase.

The RTX 5080, meanwhile, gets a small bump in minimum FPS on average. There are still a few games where it sees a relatively significant drop (Baldur’s Gate 3, both Flight Simulators, and A Plague Tale: Requiem), and also some relatively substantial gains in other games (Assassin’s Creed Odyssey, Cyberpunk 2077, F1 24, God of War Ragnarok, Hogwarts Legacy, and Star Wars Outlaws).

And it’s data like this that makes the drivers and launch of the RTX 5090, in particular, feel rushed. Improving the frame pacing and reducing stutters should be the goal. The RTX 5090, with 32GB of VRAM, appears to have some difficulties here, particularly at 1080p, suggesting the drivers were still a bit undercooked. Most likely, things will improve, but it’s also interesting that the 4080 and 4090 lost performance at 1080p as well using the new MSBDC metric.

The bottom line, as we hopefully conveyed in the 5090 and 5080 reviews, is that Nvidia’s driver and software teams still have work to do. That’s always the case, but for a new architecture, it’s especially true. We’ll be retesting the 5090 and 5080 again in the coming weeks (and months) with updated drivers, and my expectation is that 1% lows could see double-digit percentage improvements. Average FPS might see some decent gains as well, though that will probably be more on an individual game basis.

I guess Nvidia was feeling a bit jealous of Intel’s “fine wine” approach to drivers.

#Nvidias #RTX #50series #drivers #feel #halfbaked #focus #MFG